Betty stands by the Westcott Automobile: During a June 1992 visit to the Wayne County Historical Museum in Richmond, Indiana, then SSWDA President Betty Westcott Acker posed with what is said to be the first Westcott car (closer to being a motorized carriage). The vehicle was built in Richmond in 1908.

It’s All in the Book

It’s All in the Book

From “motorized carriages” in 1909 to a dramatic showing in the inaugural Indianapolis 500 in 1911 to production of over 3,000 Westcott Automobiles distributed worldwide, the 25-year story of the Westcott Motor Car Company includes adventure, style, innovation, enlightened corporate governance, a luxurious ride for the diplomatic corps, an elegant Frank Lloyd Wright designed home and a tragic end for the Westcott family.

And the full story is told in Betty Westcott Acker’s Westcott Motor Car, self-published in 1996 after a decade of research, travelling to see restored Westcott cars (and some not-so-restored), and collecting everything from dealer ads to a Spanish edition of the owner’s manual. Click the book cover to browse this 62-page view book with its cache of ad slicks, newspaper articles, and hundreds of photos. There are also stories about the business ventures of John McMahon Westcott, including the Hoosier Drill Company and the Westcott Carriage Company and a grand hotel he built in Richmond, Indiana. And then there’s John’s son Burton, who moved the automobile manufacturing to Springfield, Ohio, was a leading citizen of that city, engaged Frank Lloyd Wright to build his home, but suffered great loss and died a broken man.

The Story Behind the Book

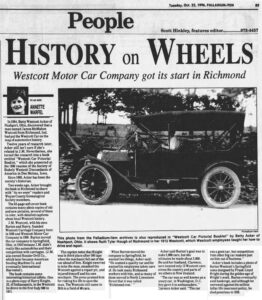

In October 1996, Betty’s research and the book were the subject of an “As we were” feature in the Richmond, Indiana Palladian-Item. Here is Annette Warfel’s feature “History on Wheels, Westcott Motor Car Company got its start in Richmond:”

In 1984, Betty Westcott Acker of Nashport, Ohio, discovered that a man named James McMahon Westcott from Richmond, Ind. had put the Westcott Car on the map of automotive history.

Twelve years of research later, Acker still isn’t sure if she’s related to J.M. Nevertheless, she turned the research into a book entitled “Westcott Car Pictorial Booklet,” which she presented at the 1996 reunion of the Society of Stukely Westcott Descendants of America in Des Moines, Iowa.

Since 1990, Acker has been the society’s historian.

Two weeks ago, Acker brought the book to Richmond to share with “As we were” readers and Wayne County Genealogical Society members.

The 62-page soft cover book contains many photocopies of old and new pictures, several of them in color, with detailed captions about local Westcott history.

J.M. Westcott, with his sons Burton and Harry, founded Westcott Carriage Company here in 1896 and Westcott Motor Car Company in 1909. Burton moved the car company to Springfield, Ohio, in 1916 because J.M. didn’t really like automobiles and their competition with carriages. (J.M. also owned Hoosier Drill Co., which later became American Seeding Machine Co. and eventually International Harvester).

The book contains some interesting historical tidbits. One is a photocopy of Harry Knight, 22, of Indianapolis, in the Westcott he drove in the first Indy 500 in 1911.

The caption notes that Knight was in third place after 196 laps when the mechanic fell out of the car ahead of him. Knight swerved to miss the man, smashed the Westcott against a repair pit, and injured himself and his own mechanic. The press praised him for risking his life to save the man. The Westcott still came in 30th in a field of 40 cars.

When Burton moved the company to Springfield, he wanted two things, Acker said: “He wanted a quality car and he wanted his employees taken care of. He took many Richmond workers with him, and so many of them moved to North Limestone Street that it was called ‘Richmond Row.’ ”

Acker said Burton’s goal was to make 5,000 cars, but she estimates he made about 3,000. She and her husband, Clarence, have located only 12 Westcott cars across the country and parts of two others in New Zealand.

“The car was so well known as a luxury car, in Washington, D.C. they gave it to ambassadors,” Clarence Acker said. “The car was a good car, but competition from other big car makers just put him out of business.”

Acker’s book includes a photo of Burton Westcott’s Springfield home designed by Frank Lloyd Wright during the golden age of Wright’s work. Burton eventually went bankrupt, and although he borrowed against his million dollar life insurance policy, he died penniless in 1926.